The most Complete Guide for visiting the Valley of the Kings

Valley of the Kings

The Valley of the Kings is an ancient Egyptian necropolis, in the vicinity of Luxor, where the tombs of most of the pharaohs of the New Kingdom (18th, 19th, and 20th dynasties), and some animals. It was popularly known to the Egyptians as Ta-sekhet-ma’at (Great Field).

It’s part of the group called Antigua Tebas with its necropolis, declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1979. The place is mystically related to the great temples of Thebes, on the eastern bank of the Nile.

Tracing a straight line from the temple of Karnak to the west, after crossing the river, it reaches Deir el-Bahari with the temple of Hatshepsut and finally the Valley of the Kings, thus materializing the east-west duality characteristic of Egyptian cosmology: the east, birthplace of the sun, is the seat of life, the fertile “Black Earth” (Kemet), territory of Horus, god of balance and the order, creator of the Egyptian civilization; on the contrary, the west, where the sun sets, is the barren, desert “Red Land”, the domain of Seth, the lord of the underworld and god of the dead.

Interesting Facts

- At first, it's possible that the Valley of the Kings was thought of as a family cemetery, not only dedicated to the kings.

- The workers who built the tombs of the pharaohs in the Valley of the Kings lived in the town of Deir el-Medina, to ensure that the location of the tombs remained secret.

- The workers of Deir el-Medina formed a religious brotherhood, by royal grace, independent of the powerful clergy of the god Amun-Re. They held the position of "servant in the Seat of Truth", which was what the tomb of the pharaoh under construction was called.

Summer daily 6AM–5PM; Winter daily 6AM–4PM.

100 Egyptian pounds for adults and 50 Egyptian pounds.

The tombs can be very hot in the summer months, so it´s best to visit the Valley of the Kings between October and April when temperatures are cooler, but still pleasantly warm.

It takes around two hours to visit to three tombs. If you add six tombs, the tour can last a total of three hours.

Moving to Luxor

(29:46 minutes)

Learn about Egypt and Luxor the Valey of the Kings Karnak Ramesseum the list goes on...

You shouldn't miss...

Luxor

Luxor Temple

Karnak

Medinet Habu

More about the Valley of the Kings

The builders of the Valley of the Kings

Thutmosis I, king of the 18th dynasty, created the first enclosure with thirty-three dwellings on the site. The origin of the workers was very diverse.

Alongside Egyptians, there were also Nubians and Hebrews, although most of them were captives of the wars of liberation against the Hyksos, the Asians who ruled the country until they were expelled from Egypt by the rulers of Thebes. The narrow, single-storey houses of Deir el-Medina were terraced on both sides of a central street.

The complex was protected by an adobe wall, somewhat higher than the flat roofs of the houses. But although it was Thutmose I who gave physical form to the enclosure, since many bricks bear his name, the idea of creating this community of workers did not come from him. It was Queen Ahmes-Nefertari, wife of Ahmose, the pharaoh who expelled the Hyksos from Egypt, and his son Amenhotep I, father of Thutmose, who conceived the project of forming a community of workers-priests to build the royal tombs. Over time, the artisans worshiped Queen Ahmés and her son, who were deified after her death.

From the beginning, the workers depended directly on the pharaoh, through his vizier, and were soon organized by categories of trades. In his village, and despite living in the middle of the desert, the influence of the Nile was always present. They even adopted a naval terminology: the inhabitants of the right side of the main street were the starboard side; those on the left side were the port side.

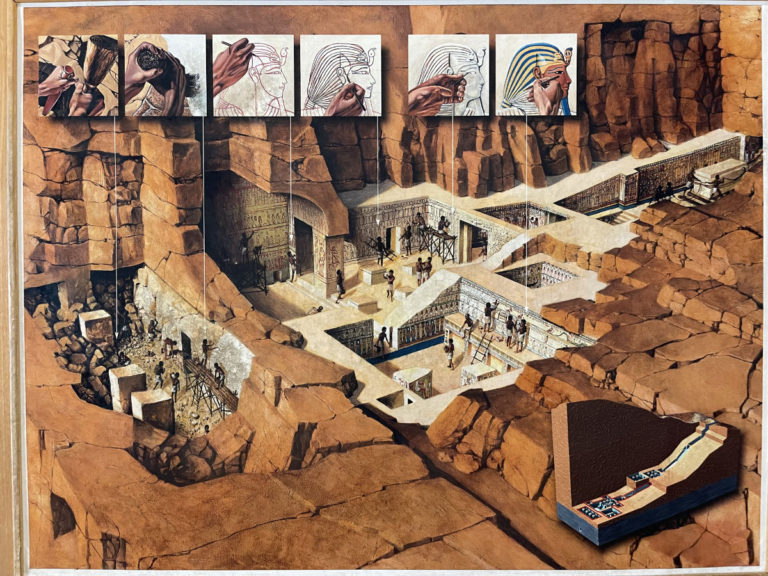

The construction of a royal tomb

The site of the royal tomb was chosen by the royal architect and approved by the pharaoh. Among the workers, bronze chisels were distributed, which were the property of the State.

Workers wrapped them in a linen sleeve with their property marks to protect their hands. They were also given rolled flax fragments and fat to fuel their rudimentary lamps.

Once the entrance of the tomb was marked, the excavation began, and the roof of the excavated tunnel was kept in the form of a vault until shortly before the plasterers covered the walls.

The tombs

To the original plan of the tomb, and according to the duration of the life of the king, rooms were added deepening in the bowels of the rock.

The fact that very few tombs were finished allows us to know all the phases of the work and the construction methods used.

Despite such hard work carried out in an almost unbreathable dusty environment, the workers were in excellent spirits. The satirical drawings and comments, collected in a thousand fragments of limestone or ceramics (ostraca), testify to this.

The royal tombs of the New Kingdom always hid their entrance to prevent looting, since the excavation had to remain secret and all traces of the grave were later erased.

The tons of limestone flakes moved away from the work site, so the topography of the Valley continually changed. Still, the accumulations of rubble alerted both ancient thieves and modern archaeologists to the existence of a royal tomb. And they allowed Giovanni Belzoni, for example, to discover in 1817 the magnificent tomb of Seti I, the second deepest in the Valley after that of Hatshepsut.

Tombs not made for Kings

In the lowest part, there are simple graves of children and fetuses deposited in baskets made of braided palm fiber. Next to these tombs alternated others, in humble wooden boxes, which, like the baskets, had previously been used for domestic needs.

Halfway up the hillside, the tombs of what was initially believed to be a community of musicians were discovered, since various musical instruments were discovered there.

On the highest levels of the hill, in the current Qurnet Murai, the tombs appeared, generally individual, of older people. The mummies rested in simple coffins that had been reused and painted again, and which, without a doubt, were a real luxury for their new owners.

Download the Valley of the Kings Travel Guide from here:

Available on Apple Books, Kindle and Google Play Books.